Watching your dog or cat go through a seizure is a very scary experience. Owners may at first think that their animal is choking or having a stroke or heart attack. The animal may merely exhibit a blank stare or the shaking / convulsions of a grand mal seizure. You may observe loss of consciousness, collapse, drooling, muscle tensing / paralysis, paddling of paws, and uncontrollable urination and defecation.

Also called ictus or convulsions, seizures are a temporary dysfunction of normal electrical activity in the brain. Seizures (particularly epilepsy, loosely defined as recurrent seizures) are the most common neurologic disorder in both cats and dogs. They start and stop abruptly and most are self-limiting, lasting about 2-3 minutes or less. Seizures that last 5 minutes or longer, or that happen 2 or more times without recovery in between are called status epilepticus (SE). SE is considered an immediate medical emergency, as are cluster seizures (CS; 2 or more seizures within 24 hours).

Among the numerous causes are tumors, infection, and exposure to toxic substances. Often the cause of the seizure is unknown, or idiopathic. Seizures can be grouped within 2 general categories:

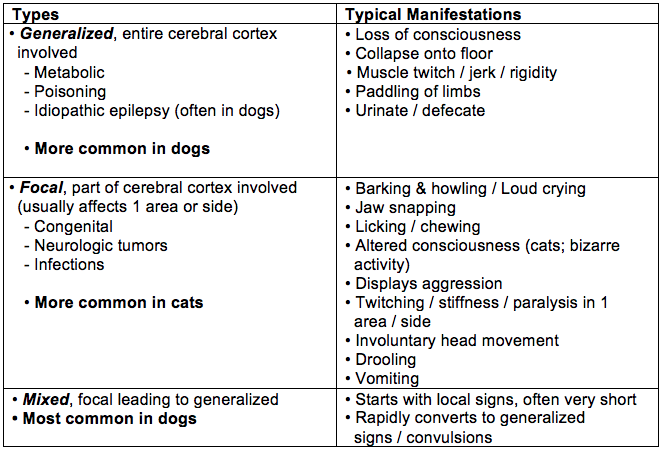

Seizures can also be grouped according to their effect on all or part of the cerebral cortex:

Seizure Types in Dogs and Cats

Sometimes your pet may exhibit a change in behavior that indicates a seizure is coming. This is called a prodrome that can happen hours or days before the seizure. Irritability, withdrawal, anxious behavior, and uncharacteristic aggression are among the prodromal signs.

What to do when your pet has seizure?

The most important thing is to remain calm and note the time the seizure begins and ends. Gently talk to your pet to help relieve its confusion and stress. If your cat or dog is near a potentially harmful object or location (table, stairs, pool, other pets, etc.), remove the object or pet. Keep away from the animal's mouth and head to avoid injuring yourself. Don't put anything in the mouth; choking on the tongue does not happen.

It's important to time the seizure. If it lasts more than 5 minutes (SE) or there are multiple seizures within 24 hours (CS), then you should immediately contact your veterinarian or pet emergency facility. It is helpful to keep a seizure diary that completely describes the episode and includes the date and seizure length. Video recording the event is an invaluable tool for diagnosis.

After the seizure (post-ictal phase) your pet may be disoriented, restless, drool, or even experience temporary blindness. If these occur contact your veterinarian.

Diagnosis

All animals need a full physical and neurologic examination by the veterinarian after a seizure, even if they've had only one. Blood tests and the owner's detailed description and timing of the event are necessary for a differential diagnosis, particularly since many different conditions can cause a seizure in cats and dogs. It is very important to give a detailed history including any potential toxin exposures. Many pet owners do not know that common ingredients in human food, such as xylitol in peanut butter for example, can be toxic to pets. If your veterinarian asks about recreational drugs in the house be honest.

Comprehensive blood tests to detect underlying disease include CBC, biochemical profile, urinalysis, and thyroid and liver functioning. If no cause is detected, the veterinarian should advise whether monitoring, treating, or further testing is indicated. Each case is different but a referral to a veterinary neurologist or internist specializing in felines or canines for further testing (eg, MRI, CT, spinal tap) may be indicated.

Dogs. Additional testing should take into account the age and breed. Dogs age 7 years or older should undergo advanced brain imaging. Tests for toxin exposure and microbial infection may be necessary based on the animal's presentation.

Cats. Seizures in cats are less common than in dogs, with focal motor seizures being more common in cats. In cats, additional tests for toxoplasmosis, FIV, FeLV, and FIP (immunodeficiency and leukemia viruses and infectious peritonitis) are needed. Advanced brain imaging (MRI or CT) may also be recommended.

Treatment

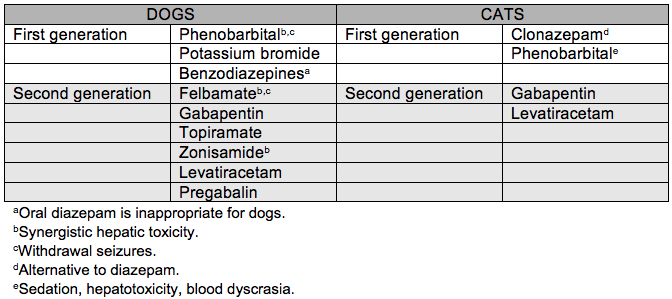

Treatment begins in pets who have had more than 1 seizure / month, cluster seizures, or status epilepticus. The goal of treatment is the elimination of or substantial reduction in the number and severity of seizures. If an underlying disease is found, its successful treatment will likely eliminate the seizures. If the underlying disease is difficult to treat but isn't likely to progress or it is epilepsy, then antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are prescribed to control the seizures. As with all treatments, benefit must be weighed against risk for adverse effects. All AEDs have different adverse effects of varying severities.

Phenobarbital is the oldest and first-choice AED for the treatment of epilepsy in dogs and cats. This drug is typically given 2 times a day. Potassium bromide is another effective drug that can be used alone or in combination with phenobarbital, particularly in animals with liver dysfunction. Both drugs are associated with side effects including sedation and impaired movement, and a significant number of dogs and cats don't respond to treatment with them. Potassium bromide is associated with adverse respiratory effects (coughing or difficulty breathing) in cats. Levetiracetam is effective in both cats and dogs, with few reported side effects. A newer extended release formula has been shown to have a long half-life in dogs, which could translate into twice-daily dosing (Veterinary Professionals learn more).

Common AEDs for Treatment of Epilepsy in Dogs and Cats

Outcome of Therapeutic Intervention

It's important to understand that a pet with idiopathic epilepsy will not be cured by treatment, but the severity and occurrences of seizures can be greatly reduced with treatment. Typically the pet is normal and can have a good quality of life in between seizures.

A diagnosis of epilepsy requires commitment of the owner for the lifetime of the pet. This entails education about the disease; strict adherence with dosing schedules (missing doses could precipitate a seizure); periodic check-ups and testing; and possible trips to the emergency room.

Professionals Learn More about Anticonvulsant Therapy