Forums

Guidance, support and wisdom to benefit and maximize the life and longevity of animals.

VetVine Client Care

Early enteral nutrition is essential in the management of critically ill dogs and cats and early implementation helps to minimize both patient morbidity and mortality.

There are a variety of ways to provide enteral nutrition but, in the hospital setting, on a short-term basis, the most common methods are by way of nasogastric (NG) and nasoesophageal (NE) tube placement. These types of feeding tubes offer several advantages: they are easy to place, veterinary technicians can learn to place them (with veterinarian verification of placement), and, depending on the patient, they can often be placed with minimal to no sedation. Some of our patients may be in very critical condition so, once stabilized, many of them may only need a local anesthetic instead of heavy sedation to permit tube placement. Another benefit of using feeding tubes for providing enteral nutrition (compared to other means) is that it's an inexpensive and efficient way to deliver nutrition to patients.

If sedation is required, drugs commonly used include butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg) and/or propofol to effect. Adjustments to the sedation protocol may be required if difficulty is encountered during placement of the tube.

Back in 2017, we reported on a novel placement technique for nasogastric and nasoesophageal tubes[1]. The technique itself is essentially the same as conventional nasogastric or nasoesophageal tube placement, but modifies the procedure by having the clinician aspirate the tube (to check positioning) at the mid-/ half-way point of insertion instead of its final positioning. This modification allows the clinician to determine - early on - whether the tube has entered the trachea or the esophagus, prior to advancing it further.

Typically, the patient is placed in sternal recumbency with the head facing forward. In large breed dogs, it can be helpful to lower or even tuck the head a bit to ease access to the esophagus. This can encourage the patient to "swallow the tube," thus facilitating its entry into the esophagus. Larger dogs are also more prone to having the feeding tube curl or loop out of the esophagus and a few adaptations help: using a stylet to provide rigidity (ensuring it does not protrude from the tube tip), choosing a larger tube size (such as 10 French), and placing the tube in the freezer briefly before placement to help it hold shape.

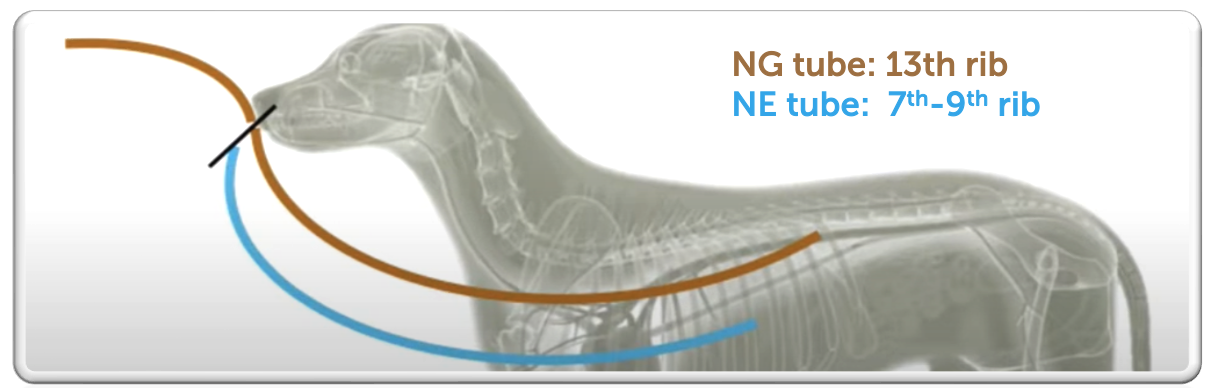

Topical anesthetics ease patient discomfort. Commonly, two or three drops of 0.5% proparacaine along with some 2% lidocaine topical lubricant are applied in both nares. Sometimes it's easier to use one side versus another and, so, by numbing both sides you'll be prepared for any needed adjustment. The lidocaine topical lubricant numbs the nose and lubricates the tube. After allowing two or three minutes for the topical medication to take effect, the tube is measured from the nose to the 13th / last rib for nasogastric placement, or from the nose to the 7th to 9th rib for nasoesophageal placement. A mark is also made at the level of the thoracic inlet to indicate the point for the mid-placement check — this is where suction is tested before advancing further.

To place the tube, the clinician should hold the muzzle (left hand for right-handed individuals) and feed the tube with the right hand. Insert the tube in a caudoventrally and medial direction into the ventral meatus of the nasal passage to pass under the nasal turbinates, reducing bleeding risk. In large dogs, pushing the external nares dorsally (pig-nosing) can help position the tube under the turbinates more easily.

Once the tip of the tube reaches the thoracic inlet, gently massaging the neck or pausing can encourage the patient to swallow.

If swallowing is observed, advance the tube to the first marked point. At this point, attach a syringe (e.g., 5 mL for cats, 10–12 mL for dogs), seal it, and aspirate to check for negative pressure. Negative pressure indicates the tube is in the esophagus and placement can continue. If you aspirate air instead, it likely indicates the tube is in the trachea. In that case, retract the tube almost fully and attempt re-placement with a more medial and ventral angle.

Once the tube reaches the final mark (depending on nasogastric or nasoesophageal target), secure it. At least one suture should be placed before taking radiographs to confirm proper placement. Three to four sutures, total, are typically used to secure a tube in place. One note about sutures ... placing sutures is the uncomfortable part of the procedure and it's often easier if you can pre-place a stay suture even before you start to place the tube. To place a stay suture, guide a 22-gauge needle through the lateral alar fold, ideally near to the alar fold to prevent curling of the tube, and feed 2-0 nonabsorbable suture through the bevel. Also pre-tying a knot on the first loop prevents cinching down the nose during final tightening, improving patient comfort. Remove the needle once the suture is in place. After the tube is positioned, secure it with a surgeon’s knot and 3 to 4 additional knots. A modified Chinese finger trap pattern — crisscrossing sutures under the tube — can help prevent sliding.

Radiographs remain the gold standard for confirming feeding tube placement and thoracic radiographs are a must. Many hospitals routinely take both lateral and DV or VD views to verify proper placement. Some veterinarians also instill a small amount (1–2 mL) of water-soluble, radiopaque contrast into the stomach to further confirm placement. There are other methods to confirm proper tube placement. Certainly, if the patient coughs during placement, that can signify that the tube is in the trachea. It's important to note, though, that not all patients will cough if the tube is placed in the trachea. Another method to check feeding tube placement is to auscult for stomach air bubbles and to aspirate the tube. This is accomplished by placing a 5cc or larger syringe onto the nasogastric tube and aspirating to check for negative suction. We expect to see negative suction if we are in the esophagus or stomach. Alternatively, you can push air into the tube using the same syringe and listen for air bubbling in the stomach with a stethoscope. However, this method can be misleading, especially in patients with pleural space disease, where gas bubbling may be heard even if the tube is not in the proper position. A more recent method described for checking tube placement is capnography. This method has greater utility in human medicine and can be cost-prohibitive for some general practices. It's not always available in every veterinary hospital.

An E-collar is essential and should be placed immediately after tube placement. While most dogs do tolerate the tubes well, it only takes one swipe for the tube to be removed.

Like any procedure, there are potential complications with nasogastric and nasoesophageal tubes. The most common complication is malpositioning of the tube into the trachea or bronchi (instead of the esophagus). While rare, this misplacement could lead to serious complications such as tracheal abscess, perforation, pneumothorax, pneumonia and, in very rare cases, death. This is especially a risk if nutrition is inadvertently administered into a tube that is mistakenly placed in the trachea. Therefore, proper placement should always be confirmed prior to use of the tube and, regardless of the method used to confirm placement, none are foolproof. In human medicine, feeding tube misplacement or malpositioning occurs in up to 1.9% of cases. The actual incidence in veterinary medicine is unknown.

[1] A novel placement technique for nasogastric and nasoesophageal tubes. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 26(4) 2016, pp 593-597. doi: 10.1111/vec.12474